FACTORS INFLUENCING VACCINE UPTAKE AMONG URBAN POOR

Bala Janaagraha

Bala Janaagraha

November 24, 2021

November 24, 2021

In Chennai, Ahmedabad, Mumbai, and Kochi, between 24-67% of the informal shack and slum dwellers have had at least their first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, a research study by Janaagraha Centre for Citizenship and Democracy, done in May-June, 2021, suggests.This data compares favourably with city and state vaccine penetration overall, as given in the Cowin dashboard, in Chennai, Ahmedabad and Mumbai. Nonetheless, the results do show that vaccine hesitancy exists in this demographic, whether it is due to issues of convenience (i.e. lack of time) or concern on side

effects or a combination of the two. Time-opportunity costs can weigh heavy on daily-wage workers, particularly in lieu of comprehensive social security systems.

Vaccine penetration

Chennai shows a considerably high vaccine penetration in the urban poor and is the highest across the four cities. It also has the largest positive difference, as compared with the city and respective state as a whole. While in Ahmedabad and Mumbai, the differences between the urban poor sample and respective city/state data is more measured; in Kochi, the proportions for the urban poor are a little lower than state and city averages.

Table 1: Vaccine uptake in 4 cities: sample vs city and state figures

| City | % taken 1st dose only | % taken 2nd dose | ||||

| Sample (Urban Poor) | City-Cowin Data | State-Cowin Data | Sample (Urban Poor) | City-Cowin Data | State-Cowin Data | |

| Chennai | 57% | 11% | 9% | 10% | 7% | 4% |

| Ahmedabad | 23% | 24% | 22% | 15% | 8% | 10% |

| Mumbai | 28% | 15% | 17% | 7% | 5% | 6% |

| Kochi | 20% | 30% | 25% | 4% | 11% | 9% |

Note: Data on vaccine uptake accessed from the COWIN dashboard on June 30, 2021, at 6.35 pm. The accumulated data on vaccination has been taken up till June 11,2021 to match the survey completion date in all four cities. The base populations were taken from the census projections as per the national commission of population. The proportion of 18+ population for each city was computed from 2011 census database and using the same proportions, the base population figures for 18+ in each city were computed.

Non-uptake of vaccinations

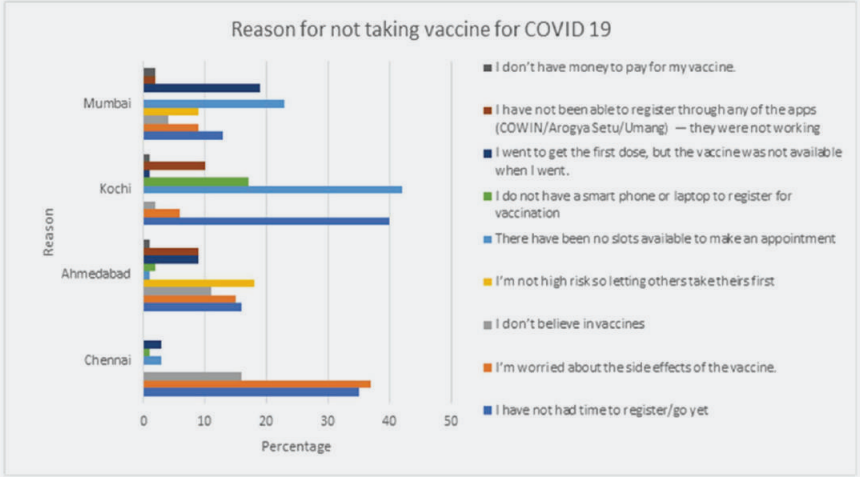

Those citizens who had not yet taken any vaccination were asked why this was the case. Possible reasons covered a range of situations from registration apps not working and internet-access constraints to non-availability of appointment slots and vaccines, time constraints, side-effects and monetary concerns.

Not having time to get the vaccination, although not the front-runner in all cities, was a consistent issue across all four, as can be seen in Figure 1. In all four cities, there were also concerns over side effects. This concern was greatest in Chennai, coupled with a proportion who do not believe in vaccines.

Neither financial concerns nor issues accessing digital infrastructure were reported as dominant reasons for the non-uptake of the vaccination by the urban poor in these cities. Only in Kochi was lack of access to a smartphone or laptop to register for the vaccine listed by a slightly larger proportion of citizens (17%). Additionally, just seven citizens, across the four cities mentioned money as a barrier to vaccine uptake.

The pervasiveness of some reasons for the non-uptake of the vaccination differed across the cities. For example, lack of appointment slots was a particular issue in Kochi and Mumbai but less so in the other cities. Additionally, the non-availability of the vaccine was an issue in Mumbai and to some extent in Ahmedabad but less so in the other cities.

Figure 1: Reasons for not taking the vaccine

Avenues of vaccine access for the urban poor

Many citizens reported they were able to get vaccinated by visiting a hospital/vaccination centre without taking a prior appointment. This is how 50% of citizens in Mumbai accessed their vaccination and 33% of citizens in Kochi, perhaps also going some way to explaining why internet access was not a particular barrier to vaccination. Additionally, the vast majority of urban poor said they were vaccinated in a government hospital or institution (87% in Kochi and 76% in Mumbai) where there is no charge for the vaccination. This may be the most likely reason why money was not noted as a major barrier to vaccination for most urban poor.

Local politicians, like corporators, have been one of the main pathways to access to vaccines in Kochi for the urban poor (30% mentioned this), possibly suggesting less need for other routes of prioritisation.

Time-poverty

Data suggests the urban poor in these cities are not systematically being left behind in the COVID-19 vaccination drive. Urban poor citizens report being able to access vaccines without prior appointment, removing the barrier of internet access, and in government institutions, removing the need for payment. Nonetheless, there is still a level of hesitancy in taking the vaccine by some, which seems to stem from lack of time and fear of side-effects. Given the nature of informal sector work, concerns of loss of wages, due to the need to go for a vaccine appointment or to recover from possible side-effects, may have impacted vaccine uptake, as some reports suggest.

Considering the research data, along with issues faced by migrant workers in India’s cities since the COVID-19 pandemic began, it is clear that a greater degree of social security is required that provides time and security to this demographic. Additionally, it highlights a need for a greater understanding of the true state of service delivery in India’s cities from the perspective of the urban poor, including migrants.

Subscribe To Our Newsletter

Sign up for our newsletter to stay up to date with the latest in active citizenship and urban governance reforms in India’s cities and towns.